While I certainly had heard of The Sand Pebbles growing up, immersed in nothing but movies.

particularly during my teenage years, I never really knew much about the flick.

All I can clearly remember was that it was a long film – it was a double-tape CBS/Fox title that sat on the

shelf of our local video store, collecting dust. The front image was one of a

navy sailor. Ad that’s about it.

Now I understand my relative ignorance of the film – despite

its nomination for 1966 Best Picture and its direction by Robert Wise, who’d

just lensed the massive hit The Sound of

Music, The Sand Pebbles is actually a pretty modest film, a low-key story

about a chapter in American history most people aren’t familiar with. And while

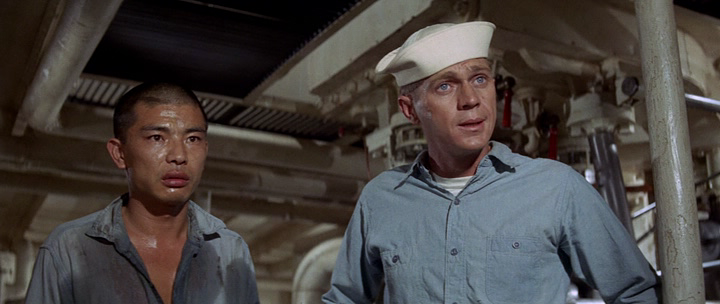

Steve McQueen stars, playing his usual steely, essentially moral but isolationist

persona, it’s not one of his more showstopping roles. But I really did get into

this one, and am glad I finally dusted it off. It’s definitely a good film –

not a great film – but a very good one.

After WWI, the

United States was a firmly imperialist power, and by the mid ‘20s it was

looking for trouble spots to watch, patrol… and potentially possess. In 1926

there was no more troubled country in the world than China, and so the U.S.

Navy sent gunboats to cruise up and down the Yangtzee. The Sand Pebbles tells the story of one such boat, the San Pablo

(nicknamed “The Sand Pebble” by its crew), and picks up when a sailor named

Jake Holman boards for duty. He’s a machinist, and he’ll be in charge of the

engine, but while impressed with its condition and overall maintenance he’s not

so pleased with how it’s being done, and especially who’s doing it: a crew of

Chinese locals called “coolies,” working strictly off he record, for no wages

but rice bowls and room and board. When this closed system results in one of

their deaths, Holman protests, but Captain Collins will hear none of it,

ordering the disgruntled seamen to train a new coolie, a young man named

Po-Han. The training goes well, and Holman takes his new protégée under his

wing, but he outside world – China – hates the Americans with a passion, and

they torture Po-Han when he is sent off the ship. Holman mercifully shoots and

kills him, but is emotionally crushed and more resentful than ever before.

But the problems don’t end there. From time to time, Holman

runs into a group of missionaries, and strikes the fancy of one in particular,

a woman named Shirley. They believe their place is with the Chinese, but it’s a

fractious relation at best; until now, the Pablo

had been under strict orders not to fight back, lest she incur the wrath of

the Chinese communists, who in turn might allow Soviet involvement. But now

Chiang Kai-shek and his emerging Republic of China could be a baddie too,

disallowing the Americans from visiting the missionaries and embrassing them in

the process. Another story, less political, involves a fallen woman named

Mally, now a high-priced prostitute who plans on using the money to pay back a

theft and begin a better life. Frenchy, another naval officer, falls in love

with the woman and finally “buys” her, and later marries her. But the uion is

short lived, as he dies from pneumonia and she is killed (offscreen), again by

the barbarous Chinamen. The murder is pinned, you guessed it, on Holman, and

again Captain Collins gives him a tongue lashing, but with rising aggression

against them from all sides, the officer takes on one final operation – the

rescue of the missionaries from China light. They fight against Chinese

defenders in order to do so, but they break through the boom and finally

arrive. Shirley and the others, apprehensive at first but giving in once they

realize their danger, escape with some of the crew, but only after Collins, and

ultimately Holman, are gunned down by snipers.

There certainly is a lot going on in The Sand Pebbles, but I didn’t mind that. My biggest issue with the

film (I’ll just cut to it now) isn’t so much the volume of plot but the

structure of it. After Po-Han’s death at roughly the one-third mark, the film

shifts from a largely single-narrative plot to a ore episodic one. Holman’s

engine-loving, coolie-exploiting hatred is suddenly cooled down itself, and as

a result the focus becomes more diffused. Now we get Holman helping Frenchy and

his girl troubles, Holman chasing after Shirley and might stay with her/might

not, French at odds against his more obedient co-crew members, etc, etc, etc…

Not that this is al entirely bad, mind you, but it does lack

the engagement of the narrative drive from the first act. I started drifting

away not only because I was no longer sure what Holman was trying to say, but

because I was no longer sure what the movie was trying to say either. When

Coliins and her crew opposed the small but nascent communist party, it’s easy

to see this as Cold War tract, as it was, after all, 1966. But it’s not, given

that all Chinese were enemies of the Pablo, and so, if you had to extrapolate

anything from Pebbles’ polemic, it

would be a general anti-imperialist attitude, a critique, perhaps, of the

American military industrial complex, which in 1926 was just getting started.

And although there are flaws with the writing of McQueen’s

character, there are no flaws with his performance. He does the character he

was best know known for – the no-nonsense loner, who always manages to be…

right. No matter what, he knows what time it is even if no one else does. I

always liked him – he’s got the patriotism with of John Wayne without the

self-parodying bombast; the isolation of Eastwood but somehow more – human,

more realistic; and the good nature of Paul Newman but less like a movie star,

like wandered in off the screen, accidentally getting caught up in the melee at

hand. As far as modern actors go, only Ryan Gosling seems to possess that

ragged cool, albeit for the post-grunge generation.

All told, a curious film. A would-be epic, were it not for

its unconventional subject matter, and fragmented treatment of it. It may have

worked great in the book, but the movies require greater focus (something Milos

Foreman knew when he adapted Ragtime).

But, glad I saw.

Rating: ***1/2