Rating: ***1/2

Spotlight made me nostalgic.

Once upon a time, primarily in the late-70s and early 80s, movies weren’t afraid to confront real topics with intelligent screenplays involving intelligent characters. They considered events involving politics, journalism, law, education, etc., and told stories that respected the intelligence of their viewers. Movies like All the President’s Men, Absence of Malice, And Justice For All and The Verdict, cinemastuff which worked our cranial cavities like professors challenging their students. We felt like adults, not just movie patrons, but folk who felt alive with the simultaneous engagement of being amply entertained and getting the chance to figure out the pieces of a puzzle. A meaningful puzzle.

Then the mid-eighties enforced the blockbuster mentality on all mainstream cinema, and those types of pictures disappeared from view, replaced with utter vapidity during the summers, and more “meaningful” works at the end of the year as Oscar bait. The low-key, incisive, cerebral film was out of fashion – any last traces of it were completely obliterated as the 90s rolled around, and digital technology destroyed the attention span necessary for the maintenance of such a picture.

So when a film comes along like Spotlight, a paper-trail story about investigative newspaper reporters uncovering the Catholic Church molestation scandal of 2001, it reinvigorates my optimism. It has all the watermarks of the films I mentioned earlier, but we’re living in a day and age when clarity and complexity are rarely seen together in a movie, so to achieve both and confront something meaningful and socially relevant is as rare as it is admirable.

Clearly he star of this film is the screenplay, and it deftly manages to lead the viewer throughout a labyrinthine, thinking-man’s whodunit with just the right dramatic rhythms. We all know the standard-issue scenes of this genre: the reporters looking at microfiche in the library, making copies, phone calls, having meetings – you know, all the exciting stuff. But the characterizations are all clear, distinct and richly-drawn, so we follow them easily, regardless of their actions.

And the dialogue is sharply resonant; it doesn’t fall for the usual histrionic clichés. We really feel like these are the conversations that go on at a major newspaper. The new editor-in-chief, played by Liev Schreiber (bearded, and looking like a 70s Richard Masur), doesn’t come in with both barrels. He doesn’t force the “Spotllight” team to do anything; rather, he suggests that to increase readership they ought to cover the stories that matter to the average subscriber. Accordingly, there’s a scene in which one reporter notices an accused priest lives nearby, all-too close to his own, vulnerable family. He goes to Keaton, unsure if he can stand waiting for the paper to strike at just the right moment with the story. Keaton, rather than respond with the standard, “We’ve got a paper to run; that’s the important thing” line we’d expect in a lesser film, instead answers, calmly, "It will happen soon." Again, real.

Some people don’t think the film’s director, Tom McCarthy, deserved his Oscar nomination in that category, but I beg to differ. He had the daunting task of juggling all the performances and scenes (and there are dozens, in this two-hour-plus movie) so they didn’t wind up as a big mess on the screen. And he does not fall prey to the unfortunate trend in wordy movies of late: having the characters talk so fast, and so artificially, that you have no idea what’s going on, and don’t particularly care either (lots of audiences mistake this for “sharp” or “witty”). McCarthy gives his dialogue plenty of breathing room – you can digest their lines, and think about their ideas afterward. Film should be no different from live theater in this regard, yet it so often is.

The film also wisely steers clear of the more graphic elements of its subject matter, realizing it would impart an entirely different tone. Not that it's not an important issue to deal with - it most certainly is - but that's a different movie (that, in fact, would be a documentary called Deliver Us From Evil, a harrowing portrait of a Catholic priest whose crimes were covered up by the church for decades). The few scenes in Spotlight that inform us of the urgency of the newspaper's mission are enough to get the point across.

A few quibbles: with so many similar, pressed-together performances, you can see which ones shine, which are serviceable, and which simply pale in comparison – it is those of the latter category (I won’t name names) which bring the whole thing down just a few pegs. And I also think a few, strategically placed moments where characters emote just a bit, perhaps from all the pressure of their jobs, would’ve served the story well. Toward the end especially we’re somewhat jaded by all the shop-talk, and it limits our investment in their quest, and ultimately whether or not they succeed.

But overall, fine work. And remember, there was a time, boys and girls, when Hollywood specialized in these sorts of films. Go back and rent a few of ‘em; you might be surprised.

Sunday, January 31, 2016

Friday, January 29, 2016

The Book Thief (2005)

Whenever I read a great book, I get mad because I didn’t write it, and The Book Thief infuriates me.

But it doesn’t last long, once I get over myself. And then I can just read and enjoy, and thank God the written word was invented so the ideas in The Book Thief can be communicated with such shattering poignancy. It’s more than just a great book – it serves a function for humanity, revisiting a dark time, a very dark time, in fresh, invigorating language. It will be read, stirring and arresting the senses of millions, for decades to come.

The narrator of the book is Death himself, having an omniscient point of view but also one that forecasts certain characters’ times of departure. Death is a pretty reliable teller, too; he just has a job to do, like anyone else, and in a way has more humanity than a good number of the heavies in the tale he tells.

Yet it’s all based on reality, and WWII in particular, and when He informs us of how busy He was at Stalingrad – “All day long as I carried the souls across it, that sheet was splashed with blood, until it was full and bulging to the earth” – we get chills. It made me think more about death both as an abstract, and death as a very real, potentially horrible possibility. And, as all great art does, it required me to consider my own mortality, and particularly in context with the millions of others, who suffered and perished in conditions far worse than my own.

*** A FEW FACTS ABOUT HIS INCIDENTAL FACTS, ***

SCATTERED THROUGHOUT THE NARRATIVE

1. They look like this

2. They’re rarely incidental

3. Don’t skip them

SCATTERED THROUGHOUT THE NARRATIVE

1. They look like this

2. They’re rarely incidental

3. Don’t skip them

Markus Zusak has precedence for his masterwork. His central conceit, along with its drolly ironic delivery of very dark matters, is of course the famous territory of legendary novelist Kurt Vonnegut. Since Vonnegut’s literary peak, countless other writers have attempted to repeat his success by emulating his style; few have succeeded. Zusak gets it right because he borrows Vonnegut’s box of toys while still retaining a style in his own right, one which manages to spin a more conventional narrative alongside the stagecraft. And the story, essentially a girl’s coming of age in a world blasted apart by the evils men are capable of inflicting upon one another, is as memorable as that of Anne Frank, the real-life counterpart to Zusak’s fictional heroine.

Liesel, the girl in question, is the title character, but her thievery is more innocuous than it sounds. So hungry for knowledge is she that she has to choice but to pilfer a book here and there – acts which broker friendships, bolster her sense of self-confidence and offer a respite from the ongoing hell around her. Death’s omniscient narration offers us a thorough understanding of her thoughts and feelings as she interacts with the assorted characters in her dramats personae: Rudy, her friend and ill-fated Hitler youth; her step-parents, long suffering Germans who, along with other residents of their street, suffer under the tyranny of their leader and the everpresent fear of death by constant aerial bombardmemts by the enemy; and Max, a Jew her family takes in who becomes an unlikely confidant throughout her trial.

This is not actually a Holocaust story. Max, is the only main Jewish character, and the concentration camps are only indirectly referenced. It focuses more on Hitler’s oppression of all people, and how violence and brutality, even when taught to empower, winds up making victims of everyone. Liesel’s train ride which starts the story, is depicted as horrifically as those which transported the Jews to their deaths. It causes the death of her brother (spurring her interest in book stealing), and scars her just as the book has scarcely begun. It is slowly revealed that her parents were incarcerated and likely murdered for being communists. Is this how a country treats its own citizens? And a little girl at that?

When we reach the inevitable conclusion, we’re almost numb. From the horror we’ve witnessed, yes. But also because it’s made so sensical, so frighteningly sane, by having it conveyed by its perpetrator. Bad, yes, but it’s not me, Death says. It’s you.

So we ask ourselves, what the hell are we doing? For a book to hold that kind of mirror up to us is a most towering accomplishment.

Labels:

Books

Thursday, January 21, 2016

The Winter of 84/85 – What a Golden Time for Elevator Rock!

| |

That describes my life, during the winter of late 1984/early ’85. I’d always loved pop music, sometimes needed pop music, and during that troubled time a movement came on the radio I’ve retrospectively dubbed “Elevator Rock.” No, it’s not as pejorative as it sounds; it’s just my moniker for a sound a few big-at-the-time rock acts made when they smoothed up their sound just a bit.

Classic rock groups have always had power ballads. One remembers Kiss’s “Beth,” Styx’s “Babe,” and Journey’s “Open Arms,” all scattered throughout the landscape of the late 70s, early 80s. But at the end of 1984, we got a nice handful of albums by such groups, and the general assortment of hits they bequeathed were, for lack of a better word, ballads. No, not “power ballads”; that term seems to describe the sort that emerged later, when hair-metal bands turned down their thunder for some meditative strains. These numbers weren’t soft by design, they just were. The mid-eighties mainstreamed a lot of edgy rock, for better or worse, but I’m not a rock critic, and I was a 14-year-old when this stuff came out. Sure, I liked Chicago and Foreigner when they were starting out, too, but I’ll always have a soft spot for their soft sounds.

You’ll see what I mean once I list them, then you’ll get an “ahh” moment. And I don’t want to get into the details of my life then, suffice to say, the radio, and my cassette tapes, offered my only true solace from the outside world.

When I went back and listened to these albums for this essay, I really felt like I went back to that time, if for just a few, scattered flashes of remembrance. The late nights at Pizza Hut, feeding the jukebox. The endless, wintry bus rides, clutching my brand-new Sony Walkman like the Hope Diamond. The rushed homework in the cafeteria, listening to the top-40 they piped in trough the intercom. And finding a way to videotape the MTV-Top 20 Countdown so I could watch the videos on my own time, usually after everyone else went to sleep.

I think I’d still like this music even if I could extract them from my memories. But I’ll never know for sure. Nor would I want to.

Here are the four key albums from that era, in order of release.

1. Chicago 17, Chicago

1. Chicago 17, ChicagoRelease date: 5/14/84

Writer/producer David Foster resurrected Chicago’s career with their previous release, Chicago 16, so it was a no-brainer to bring him back for this one. It’s clear why they were the perfect match: Fosters synth-sound, which defined the 80s more than any single artist, fit singer Peter Cetera’s falsetto pitch like a glove. With 16’s “Hard to Say I’m Sorry,” all the stars were aligned – it was a plaintive, heartfelt song, but coolly detached, too, with the piano, vocals and orchestra all falling so neatly into place. The rest of the album never quite hit the mark; still, it was an improvement over their previous, dull offerings. They were back.

“Stay the Night” was the album’s first single, peaking at #16, but it wasn’t until that Fall, when “Hard Habit To Break” rocketed to #3. Not too syrupy, not too hard (for Chicago standards), it balanced not only its tone but also its lead vocals: Cetera and future lead-vocalist Bill Champlin alternated verses with seamless proficiency – I sort of look at it as a changing of the guard, as this would be Cetera’s last album, though Champlin wouldn’t truly take over until Chicago 19, the album he owns. By the end of the year, this was the must have; whether Wall to Wall Sound and Video or the Columbia House Music Club, everyone had this one. Trust me on this.

And then the biggie: by February of ’85, “You’re the Inspiration” scored the airwaves, and no “Request and Dedication” was complete without it. Lame video, but who cared? It was just the right schmaltz, at just the right time. (It was a bleak winter, as we’d just learned four more years of Reagan were ahead of us.) And if you were about to roll your eyes at the end of the song, the “When you love somebody” outro’s completely won you over. Admit it, they did.

If it’s not Chicago’s best album (which is certainly defensible, given their avant-garde, big band-meets-rock origins), it’s definitely the apogee of the Foster era. It wisely starts off with the hard-hitting, keyboard-pounding “Stay the Night,” demonstrating the multi-tracked producing that would define the album, without neglecting the value of a good, solid hook, thanks to writer Foster.

Then comes “We Can Stop the Hurtin’” decidedly not written by Foster, and you can tell. Champlin co-wrote, and he should probably stick to singing. Not a terrible song, but it definitely slows down the momentum being so close to the beginning. Then the aforementioned “Hard Habit.” I won’t add much, except to say that it’s a nearly perfect song, starting slow and building, building, building. The fact that it’s a male duo doubly strengthens the song’s message of regret. Love the line, “Being without you, takes a lot of getting used to…” Only quibble: the end sort of peters out. Needs a tidier close.

Then “Only You,” written by Foster. Nod bad, probably one of his medium-range works. Well-produced, but missing that magical hook. Too many of these types of songs were on Chicago 16, keeping it from being fantastic. “Remember the Feeling,” written by Cetera and Champlin has good lyrics, and is arranged and produced well, but doesn’t leave you humming it. Too many modulations. Just a bridge to get to the next track:

“Along Comes a Woman,” not a Foster song, but rather co-written by Cetera. But it’s a winner (it was the first song of side two; remember, analog generation?) Perfect synth-percussion beginning, great two-part verse arrangement, solid chorus. Instrumental bridge. Nice power guitars. Great stuff.

And then ”You’re the Inspiration.” It got a lot of flack when it came out, but it was the salve for my dreary winter. I needed to hear it on my tape, and on the 98 WCAU Sunday morning countdown. I mean needed. Ironically it was also played on my hellish bus rides to school. Sort of like when they force Alex to listen to his beloved Beethoven during scenes of horror and carnage in A Clockwork Orange.

“Please Hold On”: a misfire from Foster; the less said the better. But “Prima Donna” is solid, written by Cetera, from the crappy movie Two of a Kind. I think it was a modest hit – clearly they needed filler, releasing a soundtrack song from half-a-year earlier – but no complaints. Hummable, singable, the whole nine. The album ends with the halfway decent “Once in a Lifetime,” written by longtime group trombonist J. Pankow. Plenty of synth, and Cetera even allows Pankow himself to take a verse. It ends, oddly enough, with orchestra, guitar and brass. Nothing like throwing everything in but the kitchen sink.

Chicago 17 was Cetera’s last album, and it may be their last truly great album (although I have a soft spot for 19). It’s a permanent fixture for my ’84 winter blues, and always will be. Always.

2. Vital Signs, Survivor

2. Vital Signs, SurvivorRelease date: August, 1984

Ides of March writer/vocalist Jim Peterik wasn’t content just being a one-hit-wonder for their 1971 hit “Vehicle,” so he spent the better part of the 70s founding the group Survivor. His claim that they would be the “ultimate band,” may have met with ore than a few doubters; their debut, eponymous album, released in 1980, failed to make much of a mark, and its successor, “Premonition,” wasn’t setting the world on fire either, despite giving them their first top-40 single, “Poor Man’s Son.” Some people heard it on the radio.

And one of the was Sylvester Stallone who wanted a band to record a similar song for his upcoming Rocky III. They did, and the rest is history. “Eye of the Tiger” catapulted them to the top of the charts. But with only one other hit, “American Heartbeat,” they were all dressed up with nowhere to go. Their next album, “Caught In the Act,” was a colossal bomb, and, to make matters worse, lead singer Dave Bickler took ill and had to quit the group shortly after. Would Peterik be another one-hit wonder with this group.

Nope. By the time they released their third album, Vital Signs, they knew what they were doing. With new lead singer Jimi Jamison, their sound was more fluid and unified, and, most importantly, they arrived with a new batch of killer songs. Granted, they all came at the beginning, but the album’s top-heaviness is its only major flaw. Again, attending a new, unfortunate school that fall, I needed the music to survive (pun intended), and Vital Signs supplied it.

The first track is the best. “I Can’t Hold Back” peaked at #13, and its semi-acoustic begnning, with echoey Def-Leppard leanings, perfectly befit the chilly autumn during which the single was popular. By the time we get to the thundering chorus, we’re ready for it, and couldn’t get the “I can feel you tremble when we touch” refrain out of our heads if we tried.

The synth continues (gotta love it) with “High on You,” Sure the keyboards and percussion sund all studio, but hot damn, this is a good song. (Love the leadup line: “Such complete intoxication.) You know, they just don’t write this shit anymore. Yeah, I know it’s cheesy by today’s standards, but I don’t care. I’m reminded of that scene in Boogie Nights when Dirk Diggler rents the studio in the 80s and sings “You’ve Got the Touch,” thinking it’ll be such a classic. It’s played for laughs, and dramatic irony, as we look back on it with such high-minded scorn. But I didn’t. I guess I was just as tin-eared as Dirk.

“First Night” was the last single to be released, reaching #53 in 1985. It’s not bad, and definitely underrated. Abetted by a chorus that can’t be faulted for lack of energy, it’s takes things down a notch with a couple of soulful piano interludes, and ends on as strong a note as any Survivor song.

Ahhhh, “The Search Is Over.” My summer of ’85 memories could not be complete without it. The album’s biggest single (#4), it has remained a signature 80s ballad, even included in the Broadway musical Rock of Ages. Written by founders Jim Peterik and Frankie Sullivan, it’s as perfect a song as you’ll ever hear, rock ballad or otherwise. It’s probably the chorus that makes it: it’s just not content to lay down, musically, after “…that was just my style.” Oh, no. It goes beyond that, with a double-loop, reaching for an even higher octave: “Now I look into your eyes, I can see forever, the search is over, you were with me all the while!!!” Sublime.

(Note: I have no actual musical training, but I’m trying to articulate why this song moves me so. Do not try this at home.)

“Broken Promises” is pretty standard issue (again, that midstream piano solo goes a long way). “Popular Girl” brings back the synth, though its intro sounds suspiciously like that of Bon Jovi’s “Runaway.” Catchy, though. And then, “Everlasting” really takes things down, it’s starts out meditative, like White Lion’s “When the Children Cry,” but then picks up a bit, doing some medium-range soul-searching. I actually liked this one; it’s pretty basic, but it sounds like the precursor to late-80s power balladry, a la groups like Slayer, Poison, Def Leppard (Hysteria), etc. Too bad it wasn’t a single; could’ve done well. “It the Singer Not the Song” was familiar to me as the B-Side to “The Search Is Over” (yes, we listened to B-sides back then; those 45s were all we had). The double-verse is good, and I liked it then, but now, only fair. And that’s probably being kind.

Last we get “I See You in Everyone,” which is a fitting coda, being that it throws everthing into the pot that Survivor is musically known for. Not hitting any major highs, nor sinking to unlistenable lows, it’s a straight-down-the-line track that leaves you satisfied, but still having half a notion of flipping that cassette over and playing it all over again.

And boy, did I wear this tape out. I had just really started buying tapes in earnest that summer, and this was one of the first “hard rock” albums I bought. Made me feel grown up, like I had progressed past the point of Kenny Rogers, now ready for the Poisons and Motley Crues that loomed on the horizon.

But it helped that it had the soft stuff, too.

3. Wheels Are Turnin’, REO Speedwagon

3. Wheels Are Turnin’, REO SpeedwagonRelease date: 11/5/84

The history of REO Speewagon is a lot longer and more involved. Suffice to say, they were no strangers to the easy listening arena by the mid 80s. Lead singer Kevin Cronin, despite a brief break from the band, kept REO grounded in real, raw basement rock throughout the 70s (listen to the live You Get What You Play For as proof). But with the humungazoid success of the decidedly softer offerings of “Keep On Lovin’ You” and “Take It On the Run:” from 1981’s Hi-Infidelity, the group mixed more ballads in with their jams. The follow up, Good Trouble, was only a modest success, but they were back on track with Wheels Are Turnin’, using that magic formula. And lighters were never left home from their concerts again.

To keep their street cred, they opened the album with its biggest rocker: “I Do’ Wanna Know” leaves the grammar at home to offer some pretty solid rockin’ and rollin’, harkening back to their early years while utilizing more polished production values. Then we take things down a couple of notches with “One Lonely Night,” in my opinion one of their best songs in general, written by keyboardist Neal Doughty. Featuring their trademark “Don’t take your girl for granted lyrics,” it abets the words with a killer hook, infinitely singable, hummable, memorable, and all of the above. Their songwriting mantra, Keep It Simple Stupid, serves them particularly well here. I think that comes from doing so much live work – this stuff has to be singable and playable, otherwise they don’t got a show!

“Thru the Window,” – uhh, the less said… (Well, they gave us a one-two punch opening; we shouldn’t ask for too much.) Its chorus strains, and Cronin tries hard, but it’s pretty goddamned weak. (Nice guitar work on the outro, though.) “Rock “N Roll Star” is another roots-returning number, a good bar tune but not striving for much more more. No real hook, flat chorus. You’ve heard “Live Every Moment,”: it was their last single, barely cracking the 40, with hokey, bumper-sticker lyrics and a general ho-hum musical structure. Predictably, Cronin wrote it.

But he is absolved with the even hokier “Can’t Fight This Feeling.” Sure, the lyrics are cornball, but it’s amazing what good music can compensate for. We all know it. And it’s definitely one of those songs that I “needed.” By the time that winter set in, and those early morning alarm bells roused me like an adrenaline shot jolts a zombie, I could find solace only by myself, with songs like this unspooling within my Walkman cassette player. The opening keyboards, the earnest Cronin vocals, and the trademark REO buildup before setting down again all worked together in such a magical way. Only pop music could do that.

Unfortunately, not unlike the other albums here, it sort of peters out after that. “Gotta Feel More,” a percussion-based track is standard issue. Gotta love the earnest lyrics – they at least strive for something – but the song’s title could pretty much describe the listener too. And “Break His Spell,: despite having some infectious fifties flavorings, is pretty much instantly forgettable. The album concludes with its title track, a typically lengthy (almost six-minute) coda with just the right ratio of meditative lyrics, garage rock meets prog rock sound, and extended finale, leaving the listener with both bluster and blister. A somewhat incongruous attachment, but is it really? Haven’t we come full-circle, with an REO collection of sounds that rounds out the 70s and 80s in one easy swoop?

Overall, a pretty darn fine album. Worth the 1/10 of a penny I paid to get it from the Columbia House Music Club (minus the shipping costs, of course).

4. Agent Provocateur, Foreigner

4. Agent Provocateur, ForeignerRelease date: 12/7/84

Foreigner, maybe the second best known Anglo-American collaboration in pop music after Fleetwood Mac, skyrocketed to fame in the late 70s, riding the earthy-rock trend alongside bands like REO, The Knack, Journey and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. They released their requisite softie in the form of “I Want To Know What Love Is,” and, thanks to Miss Olivia Newton-John ad her monster hit “Physical,” received the dubious distinction of having the biggest #2 hit of all time. Being #2, isn’t that bad – just ask Buzz Aldrin. On second thought, don’t.

But lead guitarist/keyboardist/founder Mick Jones and lead singer Lou Gramm didn’t have that problem with their next album, late-1984’s Agent Provocateur. I had just purchased their then-GH Records, and was caught up with all hitherto material before I delved into their new sounds. And by new sounds I pretty much mean the tune that dominated the album, “I Want To Know What Love Is.”

But first things first. We start with “Tooth and Nail,” as 80s a “hard” rock song as you’ll ever get. But damned if t doesn’t have an infectious chorus, sung with enough guitar and synth-driven blister to pump up any wine-cooler-addled partygoer within six feet of a dual-cassette boom box. Bravo, Gramm – he was sure in his prime with this one, ad his songwriting credit, with Jones, cements his cred.

They also wrote the next one, “That Was Yesterday,” the single after “I Want To Know…” It went to #12, and deservedly so. Great chorus, again with exceptional keyboard work. I thnk Gramm’s voice fit the instrumentation like a glove. I know that sounds like a very basic analysis, but I mean to say it’s not necessarily the “star”; it’s part of the musical ménage that typifies the Foreigner sound. So give Jones his due, too.

And then – the big one. “I Want To Know What Love Is,” the Jones-penned ballad spent eight weeks at number one. (Who’s laughing now, Olivia?) Everyone with the tape pretty much fast forwarded to it, or included it in a mix tape (that’s what those dual decks were for). It’s poppy, it’s bluesy, it’s, it’s… good. And of course, that chorus at the end just makes it, doesn’t it? This was the song, big in Feb of ’85, that I always recollect as being the supremest of ironies, played by the thugs on my hour-long bus ride where love, or even knowing what love is – what love could possibly be – was the furthest from anyone’s minds.

“Growing Up the Hard Way” benefits from another good power-chorus but little else. Gramm tries his darndest but it’s all about the song, and this doesn’t quite have it. Nice Genesis-esque keyboard bridge, though. “Reaction To Action” offers more of the same, with a harder riff (probably the requisite Classic Rock release).

Side two is the weaker of the two. (Didn’t really have auto-reverse back then but I’d have overrode it if we did.) “Stranger in My Own House” has loads of energy but just far too simplistic musically. (We gotta do better than AC/DC here.) Tons of synth on “Love In Vain.” Long time to get to the chorus, and what a wet noodle when we do. Strained, not worth it. “Down on Love,” the final single, is the most downtempo number; nice modulation just before the chorus, good keyboards, but kinda blah. “Two Different Worlds” continues the downward slope (dreary sums it up) and “She’s Too Tough” a would-be barn-burner, completes the picture. A wimpy end to a potentially classic entry to the Foreigner canon.

So there it is. The fearsome foursome, and I could potentially add others (the Steve Perry album was a little early, ditto Night Ranger’s “Midnight Madness”). But these four will suffice: they encapsulate an era, for me at least, and a subgenre that would have lasting impact for rock music to come. (By the late-80s, every metal act featured at least one signature ballad.) But in ’84, it was an accident of timing – one that brought to me a salvation that has resonated with me in the years since.

And will for years to come. And when magnetic tape comes back, like vinyl has now, I’ll be ready with my cassettes.

Labels:

Music

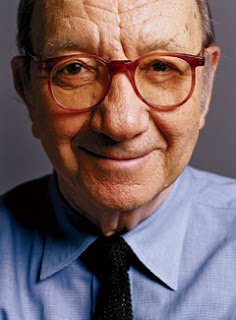

Neil Simon: Everything!

I’m about to start blogging on the entire filmography of

playwright Neil Simon, and I’m not gonna bore you with a long-winded

introduction this time. And anyways, the man’s canon oughta speak for itself –

his career spans over 60 years in both stage and screen, and he’s a mandatory

part of any conversation that includes the phrase “comedy legend.” While now

only consigned to the awareness of those-in-the-know, he was, at one time in

the late-70s and early-80s, so popular that his name was part of his titles.

And, in my opinion, he ranks up there with Larry Gelbart, Norman Lear and Woody

Allen as one of my all-time favorite comedy writers. Hearing his dialogue

performed in almost any capacity never ceases to bring a smile to my face, or cause my sides to ache.

It’s not just an ache from laughter – those guffaws come not simply from jokes but from the characters delivering those jokes. Characters based on people in his life – and our lives, too. Those friends, mothers, brothers, sisters, girlfriends, ex-girlfriends, wives – that cavalcade of assorted looneys that make up the dramatis personae of that crazy show we call life. The good times, and the bad times, or should I say, especially the bad times. The dark times when we need to laugh more than ever.

Each Simon play or movie comes directly from a part of his life. Sometimes they combine more than one part, and sometimes they focus exclusively on that part. And you can always detect what role is essentially Simon himself. Well, they say write what you know. And so he did.

But of course, I’m sure his day-to-day didn’t feature all those great one-liners he handcrafted with expert comedic precision. That comes from his sharp wit, honed on years of apprenticeship in live TV – the Golden Age, as we know it now. He worked alongside such future nobodys as Carl Reiner, Woody Allen and Mel Brooks; not such a bad graduating class. Clearly attracted to the concept of the live, Simon turned his pen toward Broadway, and the rest is history.

Looks like I’ve already come perilously close to violating the promise I made in the first paragraph. So I’ll shut up and let you go from film to film with me, starting with Come Blow Your Horn, from 1963. So let’s go.

Oscar, Felix, Corie, Paul, Paula, Elliot… and Eugene. We’re on our way!

It’s not just an ache from laughter – those guffaws come not simply from jokes but from the characters delivering those jokes. Characters based on people in his life – and our lives, too. Those friends, mothers, brothers, sisters, girlfriends, ex-girlfriends, wives – that cavalcade of assorted looneys that make up the dramatis personae of that crazy show we call life. The good times, and the bad times, or should I say, especially the bad times. The dark times when we need to laugh more than ever.

Each Simon play or movie comes directly from a part of his life. Sometimes they combine more than one part, and sometimes they focus exclusively on that part. And you can always detect what role is essentially Simon himself. Well, they say write what you know. And so he did.

But of course, I’m sure his day-to-day didn’t feature all those great one-liners he handcrafted with expert comedic precision. That comes from his sharp wit, honed on years of apprenticeship in live TV – the Golden Age, as we know it now. He worked alongside such future nobodys as Carl Reiner, Woody Allen and Mel Brooks; not such a bad graduating class. Clearly attracted to the concept of the live, Simon turned his pen toward Broadway, and the rest is history.

Looks like I’ve already come perilously close to violating the promise I made in the first paragraph. So I’ll shut up and let you go from film to film with me, starting with Come Blow Your Horn, from 1963. So let’s go.

Oscar, Felix, Corie, Paul, Paula, Elliot… and Eugene. We’re on our way!

Labels:

Neil Simon

Ex Machina (2015)

Rating: **1/2

Basically, Ex Machina is about a computer engineer who builds a female robot, then brings in a young man to see if she has the intelligence to escape.

Why in the hell would a man, ostensibly spending the better part of his entire life designing and building this thing, want to do that? So right off the bat, the film’s premise seems quite ridiculous.

In all fairness, we don’t learn this until the well into the film’s third act, when the film gets all twisty and turny with surprises and revelations that seem to be in fashion with today’s overwritten screenplays. But Ex Machina’s first hour promises some serious exploration on the subject of artificial intelligence, even though we’re introduced to Ava (the AI) far too early to develop any meaningful suspense. Combined with lush striking cinematography (of the designer’s fantastic workplace overlooking breathtaking scenery), and some nifty digital effects that are not overused, at least not at first anyway, the film starts rather intriguing.

But then it becomes clear the film isn’t much interesting in having a meaningful discussion on AI. The dialogue is heavy on information, but it’s all just window dressing: flat technospeak intended to lend credibility to the two lead characters. Instead it comes off as writer’s posturing. When Caleb, the contest winner who gets to “test” Ava, asks Nathan, the designer, why he isn’t part of a true Turing Test (when the tester doesn’t know whether or not he is talking to a computer), he isn’t given much of an answer. Nor is he for his query as to why Ava is given sexuality. Comparisons to the artist Jackson Pollack and predictions out the future of AI/human relations are dead-ends too.

And the characters aren’t particularly credible, either. At no point did I actually believe Ava was a robot, nor, for that matter, did Nathan convince me her was her builder. He spends most of the film drinking beer, lifting weights, getting pissed off, looking at all his surveillance monitors and spouting snippy phrases that are supposed to make him look intelligent. Only Caleb seems right as the contest winner, but how much praise is it that he plays a blank slate pretty well?

This surprising shallowness makes sense once we get to the big “twist,” at which time we realize it was all but a setup. And then we get some messy plot baggage involving how far Nathan has really gone with his AI toys, particularly with those of the female persuasion (really just an excuse for a lot of nudity). I won’t spoil the ending, but let’s just say things go South pretty badly for our fanatical programmer. And the very ending is clever enough, but it thusly turns the theme of the film into more of a cautionary parable than a novel-based story.

But it’s all in keeping with what the film truly wants: to be diverting entertainment. On that basis, it succeeds well enough. But it won’t be compared to AI classics like The Stepford Wives, Westworld, or more recently, A.I. or Her anytime soon.

Basically, Ex Machina is about a computer engineer who builds a female robot, then brings in a young man to see if she has the intelligence to escape.

Why in the hell would a man, ostensibly spending the better part of his entire life designing and building this thing, want to do that? So right off the bat, the film’s premise seems quite ridiculous.

In all fairness, we don’t learn this until the well into the film’s third act, when the film gets all twisty and turny with surprises and revelations that seem to be in fashion with today’s overwritten screenplays. But Ex Machina’s first hour promises some serious exploration on the subject of artificial intelligence, even though we’re introduced to Ava (the AI) far too early to develop any meaningful suspense. Combined with lush striking cinematography (of the designer’s fantastic workplace overlooking breathtaking scenery), and some nifty digital effects that are not overused, at least not at first anyway, the film starts rather intriguing.

But then it becomes clear the film isn’t much interesting in having a meaningful discussion on AI. The dialogue is heavy on information, but it’s all just window dressing: flat technospeak intended to lend credibility to the two lead characters. Instead it comes off as writer’s posturing. When Caleb, the contest winner who gets to “test” Ava, asks Nathan, the designer, why he isn’t part of a true Turing Test (when the tester doesn’t know whether or not he is talking to a computer), he isn’t given much of an answer. Nor is he for his query as to why Ava is given sexuality. Comparisons to the artist Jackson Pollack and predictions out the future of AI/human relations are dead-ends too.

And the characters aren’t particularly credible, either. At no point did I actually believe Ava was a robot, nor, for that matter, did Nathan convince me her was her builder. He spends most of the film drinking beer, lifting weights, getting pissed off, looking at all his surveillance monitors and spouting snippy phrases that are supposed to make him look intelligent. Only Caleb seems right as the contest winner, but how much praise is it that he plays a blank slate pretty well?

This surprising shallowness makes sense once we get to the big “twist,” at which time we realize it was all but a setup. And then we get some messy plot baggage involving how far Nathan has really gone with his AI toys, particularly with those of the female persuasion (really just an excuse for a lot of nudity). I won’t spoil the ending, but let’s just say things go South pretty badly for our fanatical programmer. And the very ending is clever enough, but it thusly turns the theme of the film into more of a cautionary parable than a novel-based story.

But it’s all in keeping with what the film truly wants: to be diverting entertainment. On that basis, it succeeds well enough. But it won’t be compared to AI classics like The Stepford Wives, Westworld, or more recently, A.I. or Her anytime soon.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Carol (2015)

Rating: ****

Director Todd Haynes has a real love/hate relationship with the 50s. He’s at once entranced by its style: the classy assortment of pastel hues on cars and wallpaper designs mixed up with the equally classy clothes and jazzy tunes of the time. But he also bemoans the oppression that came with it, the stifling of women and homosexuals that lay below the prettified exteriors. His brilliant 2002 film Far From Heaven showed this dichotomy. It was an ethereal mood piece, done in the style of classic film pulp from the era, but exposing all its hypocrisies and double standards.

Now, thirteen years later, Haynes treads similar turf with his newest film, Carol, also the name of a well-heeled New York lesbian (Cate Blanchett), divorcing her husband, who develops a romance with a department store clerk named Therese (Rooney Mara) around Christmastime. Carol husband is fighting her for custody of her daughter, and when he gets incriminating evidence of his wife’s dalliances with the new girl in her life, Carol is left without a leg to stand on. The girl, an aspiring photographer, is shattered when the relationship looks to be at and end, and so Carol’s dilemma appears to be a choice between the two true loves of her life.

I wouldn’t dream of disclosing the ending, but I will say it feels like a realistic ending, separate from any sense of politics or dramatic grandstanding, or get-what-you-deserve existentialism. There aren’t any obvious statements, either, like the ones in Heaven, nor does it possess that film’s savage ironies.

.No, Carol is first and foremost, a love story. The commentaries this time are subtle, meant to be subordinate to the emotional connection between Carol and Therese. What we get is a steadily involving, and evolving, love story – the impediments to its fulfillment are no different really, from those in any other film of this ilk. Haynes keeps his signature, surreal style intact, and here it works to chronicle Therese’s odyssey of bliss – but also confusion. The word “lesbian” is never once uttered in the entire film; it wasn’t part of common parlance yet, but more importantly, Therese wouldn’t know what one is. All her awareness allows her is that one human being gratifies her sexually, emotionally and intellectually. As such, she becomes the perfect metaphor for love, regardless of gender or orientation, and regardless of era

I also admire how Haynes respects his characters’ intelligence. As intolerant as his male characters are, they’re not stupid brutes either, so we don’t waste screen time having them do the ABC’ of same-sex relationships. And Therese, though depicted as a shy ingénue, also knows want she wants, and doesn’t have to go through the whole rigmarole of being seduced. This is the work of a mature artist, dealing with once-taboo subject matter just as maturely.

And I thank God we still have filmmakers like this, apart from the sniveling, schoolboyish (and generally male) purveyors of Hollywood product these days. Hayes’ films are handcrafted works of both style and clarity – and both in the service of character. When you watch something from folks of this grain, you get a visceral feeling of passion. They want to tell these stories. Badly. And I, for one, want to watch.

Director Todd Haynes has a real love/hate relationship with the 50s. He’s at once entranced by its style: the classy assortment of pastel hues on cars and wallpaper designs mixed up with the equally classy clothes and jazzy tunes of the time. But he also bemoans the oppression that came with it, the stifling of women and homosexuals that lay below the prettified exteriors. His brilliant 2002 film Far From Heaven showed this dichotomy. It was an ethereal mood piece, done in the style of classic film pulp from the era, but exposing all its hypocrisies and double standards.

Now, thirteen years later, Haynes treads similar turf with his newest film, Carol, also the name of a well-heeled New York lesbian (Cate Blanchett), divorcing her husband, who develops a romance with a department store clerk named Therese (Rooney Mara) around Christmastime. Carol husband is fighting her for custody of her daughter, and when he gets incriminating evidence of his wife’s dalliances with the new girl in her life, Carol is left without a leg to stand on. The girl, an aspiring photographer, is shattered when the relationship looks to be at and end, and so Carol’s dilemma appears to be a choice between the two true loves of her life.

I wouldn’t dream of disclosing the ending, but I will say it feels like a realistic ending, separate from any sense of politics or dramatic grandstanding, or get-what-you-deserve existentialism. There aren’t any obvious statements, either, like the ones in Heaven, nor does it possess that film’s savage ironies.

.No, Carol is first and foremost, a love story. The commentaries this time are subtle, meant to be subordinate to the emotional connection between Carol and Therese. What we get is a steadily involving, and evolving, love story – the impediments to its fulfillment are no different really, from those in any other film of this ilk. Haynes keeps his signature, surreal style intact, and here it works to chronicle Therese’s odyssey of bliss – but also confusion. The word “lesbian” is never once uttered in the entire film; it wasn’t part of common parlance yet, but more importantly, Therese wouldn’t know what one is. All her awareness allows her is that one human being gratifies her sexually, emotionally and intellectually. As such, she becomes the perfect metaphor for love, regardless of gender or orientation, and regardless of era

I also admire how Haynes respects his characters’ intelligence. As intolerant as his male characters are, they’re not stupid brutes either, so we don’t waste screen time having them do the ABC’ of same-sex relationships. And Therese, though depicted as a shy ingénue, also knows want she wants, and doesn’t have to go through the whole rigmarole of being seduced. This is the work of a mature artist, dealing with once-taboo subject matter just as maturely.

And I thank God we still have filmmakers like this, apart from the sniveling, schoolboyish (and generally male) purveyors of Hollywood product these days. Hayes’ films are handcrafted works of both style and clarity – and both in the service of character. When you watch something from folks of this grain, you get a visceral feeling of passion. They want to tell these stories. Badly. And I, for one, want to watch.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)